Cos X The Gentlewoman | Modernist Architectural Tour of London

Last September I joined COS x The Gentlewoman magazine on the London leg of their 'Glimpses of The Future' architectural tour. Led by architectural historian Joe Kerr, we hopped onboard a 1960s Routemaster and headed to 5 top Modernist locations, all connected through the theme of social housing. My interpretation of the guide is a little more basic as an enthusiastic newbie so you'll have to forgive me, but nevertheless, I hope this will give you a taste of some of London's modernist treasures.

Last September I joined COS x The Gentlewoman magazine on the London leg of their 'Glimpses of The Future' architectural tour. Led by architectural historian Joe Kerr, we hopped onboard a 1960s Routemaster and headed to 5 top Modernist locations, all connected through the theme of social housing. My interpretation of the guide is a little more basic as an enthusiastic newbie so you'll have to forgive me, but nevertheless, I hope this will give you a taste of some of London's modernist treasures.

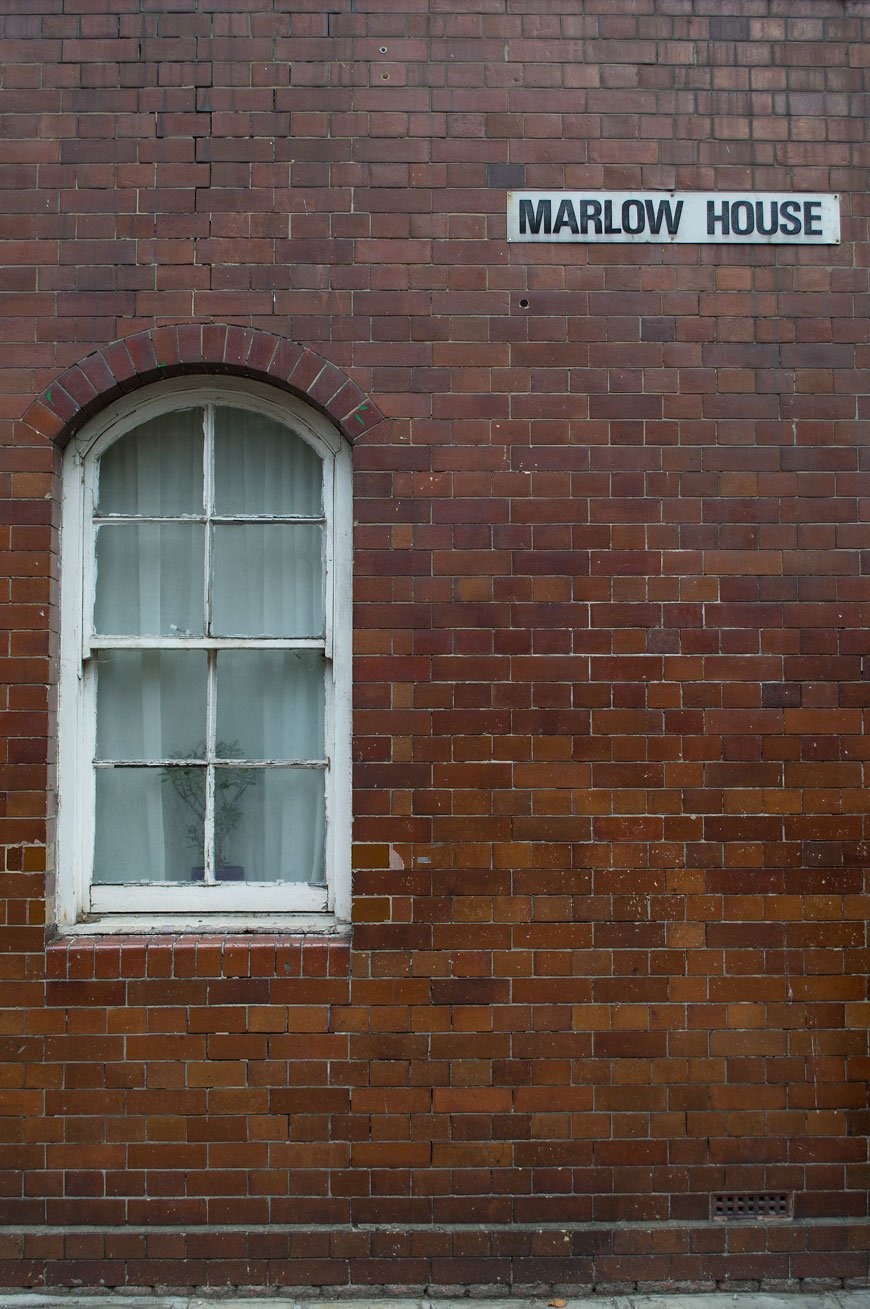

The Boundary Estate | Est 1900, designed by London County Council Architects

First up, the Boundary Estate, one of the world's oldest municipal housing projects leading to the Arnold Circus at its centre. If you're a Shoreditch regular, then it's likely you're already familiar with it. Prior to its creation, an overcrowded slum stood on this site, home to over 5,000 people living in the most extreme squalor. The majority of these people came from trade backgrounds - shoemakers, silk weavers, dustmen, all of them crammed into these tumbledown buildings.In order to improve the basic living conditions, the LCC committed to building a new estate in 1893 with running water, proper sanitation and better living quarters with most tenements accommodating two to three rooms. Rubble from the surrounding area became the foundations for a Japanese style bandstand which stands at the centre surrounded by seating. From the bandstand, you can see a full 360-degree view of the estate with its grand red brick, tiled walls, large windows and open, green spaces. A world away from its origins. There were shops, a laundry, workshops and two schools available to residents - compared to what stood here before, this was a radical and much sought after place to live.When the finished estate was opened up, however, it wasn't the original tenants who moved back in. They were in fact displaced further into the depths of the East London slums around Dalston and Bethnal Green, giving way to a more affluent worker; policemen, clerks and nurses who could afford the upkeep. It's a familiar story of gentrification, isn't it?

First up, the Boundary Estate, one of the world's oldest municipal housing projects leading to the Arnold Circus at its centre. If you're a Shoreditch regular, then it's likely you're already familiar with it. Prior to its creation, an overcrowded slum stood on this site, home to over 5,000 people living in the most extreme squalor. The majority of these people came from trade backgrounds - shoemakers, silk weavers, dustmen, all of them crammed into these tumbledown buildings.In order to improve the basic living conditions, the LCC committed to building a new estate in 1893 with running water, proper sanitation and better living quarters with most tenements accommodating two to three rooms. Rubble from the surrounding area became the foundations for a Japanese style bandstand which stands at the centre surrounded by seating. From the bandstand, you can see a full 360-degree view of the estate with its grand red brick, tiled walls, large windows and open, green spaces. A world away from its origins. There were shops, a laundry, workshops and two schools available to residents - compared to what stood here before, this was a radical and much sought after place to live.When the finished estate was opened up, however, it wasn't the original tenants who moved back in. They were in fact displaced further into the depths of the East London slums around Dalston and Bethnal Green, giving way to a more affluent worker; policemen, clerks and nurses who could afford the upkeep. It's a familiar story of gentrification, isn't it?

Bevin Court | Est 1954, designed by Berthold Lubetkin.

There's something so very satisfying about the symmetry of our next stop - Bevin Court, a Lubetkin wonder with a controversial backstory. This example of post-war architecture was built on the site of bombed-out Holford Square, once home to Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin. The site was briefly home to a memorial dedicated to Lenin and Lubetkin had intended to name the building Lenin Court. In the years to come, however, the memorial was repeatedly vandalised by anti-communists and eventually had to be removed. In an act of defiance, fellow Russian Lubetkin would allegedly have the statue buried under the central staircase. As British and Russian relations worsened and the Cold War intensified, the completed building was renamed Bevin Court in honour of anti-communist foreign secretary Ernest Bevin. You can imagine how Lubetkin felt about that!

There's something so very satisfying about the symmetry of our next stop - Bevin Court, a Lubetkin wonder with a controversial backstory. This example of post-war architecture was built on the site of bombed-out Holford Square, once home to Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin. The site was briefly home to a memorial dedicated to Lenin and Lubetkin had intended to name the building Lenin Court. In the years to come, however, the memorial was repeatedly vandalised by anti-communists and eventually had to be removed. In an act of defiance, fellow Russian Lubetkin would allegedly have the statue buried under the central staircase. As British and Russian relations worsened and the Cold War intensified, the completed building was renamed Bevin Court in honour of anti-communist foreign secretary Ernest Bevin. You can imagine how Lubetkin felt about that!

With austerity in full effect and construction budgets low, Lubetkin and his practice Tecton were forced to strip back amenities and focus solely on the absolute basics. The prefabricated concrete is truly spectacular. In contrast to the straight lines of the exterior, fluid curves make up the central stairwell and hallway spaces, encouraging social interaction. Open to the elements, the large windows offer views across the city and surrounded by well-established trees and planting. Not your average social housing scheme given its time and hardly a surprise that Bevin Court became a Grade II listed building in 1988.

With austerity in full effect and construction budgets low, Lubetkin and his practice Tecton were forced to strip back amenities and focus solely on the absolute basics. The prefabricated concrete is truly spectacular. In contrast to the straight lines of the exterior, fluid curves make up the central stairwell and hallway spaces, encouraging social interaction. Open to the elements, the large windows offer views across the city and surrounded by well-established trees and planting. Not your average social housing scheme given its time and hardly a surprise that Bevin Court became a Grade II listed building in 1988.

Royal College of Physicians | Est 1964, designed by Denys Lasdun.

If you ever find yourself wandering the east side of Regent's Park, make an effort to visit the RCP building. Yes, you're actually allowed to look inside this one, though for me the magic of the building is the outside. Not a piece of social housing in the traditional sense, it is a place of work, so that counts. Completed in 1964, the building houses a museum, library and lecture halls as well as a stunning medicinal garden. Visit at the right time of year and you might even spot the massive lemons growing there. As big as your head. Literally.Traditionally housed in classically designed, historic buildings, it was quite the curveball that the RCP commissioned Brutalist architect Sir Denys Lasdun to design their new location. An architect inspired by the work of Le Corbusier, Lasdun spent time at Tecton, Lubetkin's practice as well as with Wells Coates whose Isokon Building was to be our final location on the tour.The intended new site of the RCP was Someries House, a building designed by John Nash but severely damaged during the war. Demolition wasn't completely out of the question at this point, so long as the new building reflected the Regency style of the surrounding terraces. When it came to appointing an architect for the job, the brief was clear - the new location had to look elegant and accommodate the everyday function of the RCP itself.Lasdun was unapologetic in his approach to designing the new building. It would not be in the classical style, yet it would still acknowledge the history of its surroundings which are seen through cleverly placed sight lines out at the terraces from inside the building. Perhaps it was Lasdun's daring, modernist approach that sold the idea to the royal college - after all, the history of medical practice had evolved so much over the past 400 years, it would seem right to represent a new, post-war era for the RCP with its architecture.

If you ever find yourself wandering the east side of Regent's Park, make an effort to visit the RCP building. Yes, you're actually allowed to look inside this one, though for me the magic of the building is the outside. Not a piece of social housing in the traditional sense, it is a place of work, so that counts. Completed in 1964, the building houses a museum, library and lecture halls as well as a stunning medicinal garden. Visit at the right time of year and you might even spot the massive lemons growing there. As big as your head. Literally.Traditionally housed in classically designed, historic buildings, it was quite the curveball that the RCP commissioned Brutalist architect Sir Denys Lasdun to design their new location. An architect inspired by the work of Le Corbusier, Lasdun spent time at Tecton, Lubetkin's practice as well as with Wells Coates whose Isokon Building was to be our final location on the tour.The intended new site of the RCP was Someries House, a building designed by John Nash but severely damaged during the war. Demolition wasn't completely out of the question at this point, so long as the new building reflected the Regency style of the surrounding terraces. When it came to appointing an architect for the job, the brief was clear - the new location had to look elegant and accommodate the everyday function of the RCP itself.Lasdun was unapologetic in his approach to designing the new building. It would not be in the classical style, yet it would still acknowledge the history of its surroundings which are seen through cleverly placed sight lines out at the terraces from inside the building. Perhaps it was Lasdun's daring, modernist approach that sold the idea to the royal college - after all, the history of medical practice had evolved so much over the past 400 years, it would seem right to represent a new, post-war era for the RCP with its architecture.

As you approach the front of the building, you're met by a breathtaking tile clad overhang, which houses the library. Made from reinforced steel concrete, this section is supported by three columns, under which steps lead up to the foyer and on into an open space with a central staircase. Materials used on the exterior are continued inside, including the austere brick and marble-clad walls.A monochrome wonder, Lasdun's design is sympathetic to its surroundings, despite its ground-breaking, modernist appearance. I could wax lyrical about this building until I'm blue in the face, but you can see for yourself what a marvel it is. And Grade 1 listed too.

As you approach the front of the building, you're met by a breathtaking tile clad overhang, which houses the library. Made from reinforced steel concrete, this section is supported by three columns, under which steps lead up to the foyer and on into an open space with a central staircase. Materials used on the exterior are continued inside, including the austere brick and marble-clad walls.A monochrome wonder, Lasdun's design is sympathetic to its surroundings, despite its ground-breaking, modernist appearance. I could wax lyrical about this building until I'm blue in the face, but you can see for yourself what a marvel it is. And Grade 1 listed too.

Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate | Est 1978, designed by Neave Brown.

Not surprisingly my favourite and I think you can guess why (I'll give you a clue - PLANTS). The Alexandra Estate, or Rowley Way as it's commonly known feels like it has its own micro-climate thanks to the ingenious cast concrete structure, designed by Neave Brown. A departure from the more popular high rise, the estate consists of two rows of four-storey blocks facing onto a central street, with higher eight-storey blocks further back. This valley like structure keeps out much of the harsh weather, allowing an array of planting to thrive here. Noise pollution from the railway line behind is kept out as the structure acts as a sound barrier.

Not surprisingly my favourite and I think you can guess why (I'll give you a clue - PLANTS). The Alexandra Estate, or Rowley Way as it's commonly known feels like it has its own micro-climate thanks to the ingenious cast concrete structure, designed by Neave Brown. A departure from the more popular high rise, the estate consists of two rows of four-storey blocks facing onto a central street, with higher eight-storey blocks further back. This valley like structure keeps out much of the harsh weather, allowing an array of planting to thrive here. Noise pollution from the railway line behind is kept out as the structure acts as a sound barrier. It's definitely an unconventional beauty, drawing you in to explore its social spaces and admire the tropical planting. We had a few strange looks from local residents who stopped and asked what we were up to. They weren't surprised to see us on a tour, though they found it strange that people would visit to admire it. One resident had lived there for over 20 years and raised her four children in a safe and happy environment. Every home is light and spacious for family living with balconies and underground parking facilities. This is how social housing should be - well considered, good quality living, not hastily thrown up to cut corners. I'm looking at you Kensington and Chelsea Council.

It's definitely an unconventional beauty, drawing you in to explore its social spaces and admire the tropical planting. We had a few strange looks from local residents who stopped and asked what we were up to. They weren't surprised to see us on a tour, though they found it strange that people would visit to admire it. One resident had lived there for over 20 years and raised her four children in a safe and happy environment. Every home is light and spacious for family living with balconies and underground parking facilities. This is how social housing should be - well considered, good quality living, not hastily thrown up to cut corners. I'm looking at you Kensington and Chelsea Council.

Unfortunately for Brown, this project drew a lot of attention for all the wrong reasons due to the complicated construction methods, becoming one of the most expensive examples of social housing. It wasn't until last year that Brown won the RIBA Royal Gold Medal in recognition of his contribution to architecture. Richly deserved too.

Unfortunately for Brown, this project drew a lot of attention for all the wrong reasons due to the complicated construction methods, becoming one of the most expensive examples of social housing. It wasn't until last year that Brown won the RIBA Royal Gold Medal in recognition of his contribution to architecture. Richly deserved too.

Isokon Building | Est 1934, designed by Wells Coates.

Last stop on the tour - Wells Coates' masterpiece, the Isokon building. With the September sun highlighting her curved form, we joined resident of the Isokon Penthouse and director of the Isokon Gallery Trust, Magnus Englund.The Lawn Road Flats as they were originally known, were designed by Canadian architect Coates with the young professional in mind. Influenced by Bauhaus design, the building was commissioned by husband and wife Molly and Jack Pritchard, owners of modernist design studio, Isokon. Likened to an ocean liner, a look referenced heavily within 1930s design, the building features 34 flats marketed with all mod-cons. Ideal for those too busy to cook and clean, there were staff quarters, kitchens, a dumbwaiter and the Isobar downstairs for communal gatherings. The height of 30s glamour.Built-in, plywood furniture designed by the Isokon Furniture Company provided a simplistic, straightforward way of living or "equipment for the living of a free life". With an illustrious past, the list of previous residents reads like a dream dinner party, including Agatha Christie, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer.There is much to delve into within the history of this building - Pritchard's involvement with Isokon and the community of Europe's modernist movers and shakers, how well the building faired over its 80s years. It might be better told through the building itself though, which houses a museum dedicated to the life of the building and the people who brought it into being.Thank you to The Gentlewoman and COS for this wonderful experience. You can follow the Glimpses of the Future architectural tour here (bearing in mind that some residences can't be accessed from the inside).If you fancy getting involved with The Gentlewoman, you can join their club for exclusive events and tours.

Last stop on the tour - Wells Coates' masterpiece, the Isokon building. With the September sun highlighting her curved form, we joined resident of the Isokon Penthouse and director of the Isokon Gallery Trust, Magnus Englund.The Lawn Road Flats as they were originally known, were designed by Canadian architect Coates with the young professional in mind. Influenced by Bauhaus design, the building was commissioned by husband and wife Molly and Jack Pritchard, owners of modernist design studio, Isokon. Likened to an ocean liner, a look referenced heavily within 1930s design, the building features 34 flats marketed with all mod-cons. Ideal for those too busy to cook and clean, there were staff quarters, kitchens, a dumbwaiter and the Isobar downstairs for communal gatherings. The height of 30s glamour.Built-in, plywood furniture designed by the Isokon Furniture Company provided a simplistic, straightforward way of living or "equipment for the living of a free life". With an illustrious past, the list of previous residents reads like a dream dinner party, including Agatha Christie, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer.There is much to delve into within the history of this building - Pritchard's involvement with Isokon and the community of Europe's modernist movers and shakers, how well the building faired over its 80s years. It might be better told through the building itself though, which houses a museum dedicated to the life of the building and the people who brought it into being.Thank you to The Gentlewoman and COS for this wonderful experience. You can follow the Glimpses of the Future architectural tour here (bearing in mind that some residences can't be accessed from the inside).If you fancy getting involved with The Gentlewoman, you can join their club for exclusive events and tours.